Without the Conversation, There is no Value Pricing

For over ten years I have been on a quest – along with Ron Baker and the Fellows at the VeraSage Institute – to assist professionals in implementing value pricing in their organizations. In working with firms of all shapes, sizes and sectors, one of the most common challenges I hear about is that of professionals’ ability to engage with a customer or prospect in what we call “The Value Conversation.”

The trouble is that without the ability to have this conversation, value pricing is dead on arrival. This may be obvious, but let me explain why.We define value pricing as “a price wherein the primary, but not sole determining influence in the development of that price is the perceived value to the customer.” If one accepts this definition, then it is clear that without knowing what the perceived value is, there is no way to use it as the primary influence in the setting of that price. Without the value conversation, there can be NO value pricing.

So why do professionals not engage in the value conversation? The answer is simple – it is difficult to do. There is no question that the value conversation requires a high level of skill, the ability to focus deeply, and lots of practice.Dan Morris, one of the co-founders of VeraSage – and someone I consider to be at a Jedi Master level in regard to the value conversation – says he does an adequate job only 30 percent to 40 percent of the time. It would seem then that, like a Major League Baseball hitter, a .300 lifetime batting average is grounds for inclusion in the Hall of Fame. Like the .300 hitter, the skill of the value conversation is within reach of all professionals.

To conduct an effective value conversation one has to hone one’s skills in the following three areas: inquiry, moving off the solution, and getting to value. The rest of this article will consider the first two.

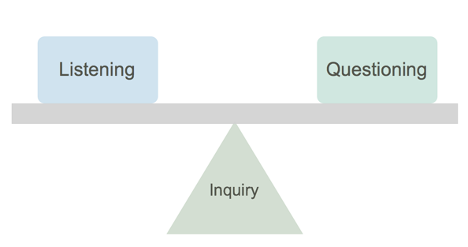

Inquiry

First, let me define inquiry as the skill of balancing one’s ability to deeply listen and ask effective questions. It is beyond a mindset. Rather, it is a state of being. One must be relaxed and genuinely curious. One’s motivation must not be about getting the sale, but a true and intense curiosity about the prospect’s or customer’s situation. One’s intention must be to develop questions that will help the person make the best possible decision for them, even if that decision is not to continue the relationship with you.

Deep listening, or what psychoanalysts call active listening, requires an enormous amount of concentration. We must try to dial down our own thinking about what the customer is saying and instead be more attuned to understanding and clarifying what he or she is saying. As both Stephen Covey and St. Francis have said, we should, “seek first to understand before we seek to be understood.”

The key skill in inquiry is the ability to think about, and process in one’s mind, the best next question to ask as the customer is speaking, instead of allowing ourselves to think about how we will go about solving the customer’s problems at this time.

If you can’t ask good questions, you have nothing to listen to. If you can’t truly listen, you can’t ask good questions.

Move Off the Solution

Second, one must be able to deftly “move off the solution,” as Mahan Khalsa says in his great book, Let’s Get Real or Let’s Not Play: Transforming the Buyer/Seller Relationship. In many cases, this requires professionals to fight their inner desire to talk about and even solve the customer’s problem during the initial conversation about the problem.The idea of moving off the solution is to gain insight into the true nature, and eventually the perceived value, of the problem. Solutions have no inherent value – instead they derive their value from the problems that they solve. The trouble is, professionals really like to solve problems, even though the problems might have low or no value to the customer. Professionals tend to have the “disease” of solutionism.

Solutionism is very much akin to a substance abuse problem. In fact, the brain function is almost identical. Professionals get a “high” – a rush of the hormones oxytocin and dopamine – when they solve a customer’s problems. We become addicted to it. The trouble is this interferes with our ability to have the value conversation. Like any addiction it comes at a significant price.Moving off the solution is the antidote to this disease.Moving off the solution has three elements:

Assuaging – the professional must make the customer feel good about the question that is being asked.

Pivoting – the professional must pivot the conversation away from talking about the solution.

Closing – the professional must ask the customer permission to have a conversation about the problem and not the solution.

This is often done in just a few sentences. For example, a customer emails saying, “We are interested in adding CRM capabilities to our system. How much will that cost?”

A successful move would sound something like this: “Thanks for your email. As you know we have a number of customers using CRM. However, what we have found is that CRM means something a little bit different in every organization. Would it be okay with you if I scheduled a call to talk a little bit about what CRM means to you?”

Notice that all three elements are addressed.

Assuaging – “Thanks for your email. As you know, we do have a number of customers using CRM.”

Pivoting – “However, what we have found is that CRM means something a little bit different in every organization.”

Closing – “Would it be okay with you if I scheduled a call to talk a little bit about what CRM means to you?”

Of these three, I cannot over emphasize the importance of the third, and that it be formed as a closed probe question. A closed probe question is one designed to solicit a “Yes” or “No” answer. Too often, I have heard professionals immediately jump to asking an open probe question such as, “Why do you think you need CRM?”

More often than not the customer feels slighted, at best, or intruded upon at worst. This shuts down even the possibility of a value conversation. The closing is important because the professional is asking permission to not answer the prospect’s question, “How much does it cost?” Please note that we are not doing this to be manipulative, but rather because we truly seek to help the customer make the best possible decision.

What’s Next?

After the successful move off the solution, the professional must then gain an understanding of the perceived value to the customer. The methods needed to do this are beyond the scope of this article, so I will instead recommend again that you read Mahan Khalsa’s Let’s Get Real or Let’s Not Play.

Having the value conversation with a prospect or customer is a non-negotiable step in the path to value pricing. It is not easy to do because if requires us to change our way of thinking about how we listen and what we say in the earliest conversations we have with them.

That said, it is not beyond the ability of any professional to learn these skills. As demonstrated here, they are simple, but they are just not easy. It takes patience with oneself and practice, but once one gets comfortable with these skills, value pricing will be within your reach.